Last semester I blogged about a couple of experiments with incorporating library searches and materials into my US History II survey class. I teach it every semester so I’m always tweaking. This term I started off in an overcrowded, overheated classroom with an oversubscribed class list, so I begged a room switch and I ended up with one of the campus’s best-kept secrets: a classroom that has been configured to the liking of the art history professors in the Visual & Performing Arts department. Ah. Classroom nirvana. Big, odd-shaped, with individual desks, no windows, warm in winter but not stifling, with soothing adjustable lighting, a HUGE screen that’s permanently down, and whiteboards on a different wall (in most classrooms, we have the genius design of having screens that, when pulled down, cover the whiteboards). And bonus: it’s in the library building, one floor down.

This week was our third “workshop day” when I have students play the historian. The first two were laptop-based, using digital archives and multimedia. But for this one, I wanted them to use… wait for it… actual books (or articles). Also, the first two were in the middle of a unit, and this one was at the beginning, so I thought I’d use it for getting them curious about some of the upcoming topics and to identify what they’re interested in learning about the 1930s. I also want my students to use the library. For reasons too complicated to go into here, there is not a strong culture of library use on our campus. And “kids these days,” or at least the kids we tend to get, don’t read a lot. It sounds like this is true elsewhere, too.

Step one: give a pretest. It was pretty basic, just a blank matrix with instructions to fill something in each box. Of course since it’s the beginning of the unit, there were a lot of blanks. Heck, if *I* took it I think there would be blanks. Bonus: this creates an outline for what we all should know by the end of the unit.

- One cause of the Great Depression (besides the stock market crash)

- Something specific about life during the Depression (1929-1932)

- A number that represents a specific economic statistic about the Depression

- One thing President Hoover did to try to alleviate the Depression

- A person who was a “New Dealer†in FDR’s cabinet or a government agency

- A New Deal agency

- A cultural product of the 1930s

- Someone who opposed or criticized the New Deal

Step two: formulate a research question. I asked them to look at their matrix and think about which ones they knew less well, and to formulate a specific research query for today’s classtime.

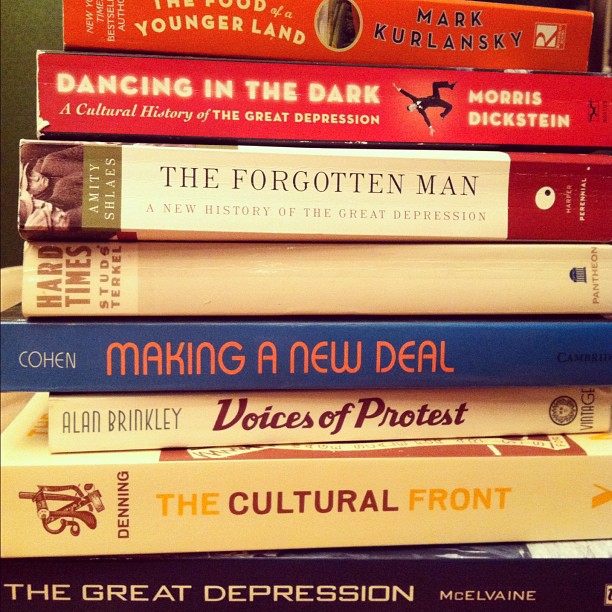

Step three: hit the books – I gave them 3 options. Option 1:  a stack of books about the 1930s from my own shelves (photo). Option 2: go find a book upstairs in the library; I gave a quick 10-minute tutorial on using the library’s online catalog, and introduced the idea of Library of Congress subject headings. Option 3: use the library’s databases to find relevant scholarly articles; I demo’d how to keyword-search in one of our databases (we don’t have much for history, so I just used the basic Academic Search from EBSCO Host – in a dream world, we would have full JSTOR and America: History and Life, but we’ve got neither). They had about half an hour to locate something and spend time reading it. I banned the use of Google, Wikipedia, or any other website besides the University’s library site.

a stack of books about the 1930s from my own shelves (photo). Option 2: go find a book upstairs in the library; I gave a quick 10-minute tutorial on using the library’s online catalog, and introduced the idea of Library of Congress subject headings. Option 3: use the library’s databases to find relevant scholarly articles; I demo’d how to keyword-search in one of our databases (we don’t have much for history, so I just used the basic Academic Search from EBSCO Host – in a dream world, we would have full JSTOR and America: History and Life, but we’ve got neither). They had about half an hour to locate something and spend time reading it. I banned the use of Google, Wikipedia, or any other website besides the University’s library site.

Step four: write/reflect/keep a log of research. I provided a blank worksheet with space to record the research topic & question, what they did, which books/articles were consulted, and whether they got their question answered. I emphasized that the point of the workshop was the search, not the answer. The worksheet was due at the end of the class and it counted as the attendance for the day (to prevent folks from just heading off to lunch instead of the stacks).

Most of the class disappeared upstairs for the next half hour. I stayed in the classroom as a resource. Maybe half a dozen stuck around, using their laptops to find articles or reading the books I’d brought. The rest infiltrated the stacks and when they turned in their sheets at the end of class, I got a chance to talk with each student about what they’d found.

The best part was: some of them came back with that little light on behind their eyes – “I found this one book and I got really interested in it, I almost lost track of time.” One got absorbed in a book about 1930s comic strips. Another lost himself in a book about films of the 1930s. Hopefully a few books got actually checked out! One asked to borrow one of my books to keep reading. Two students had drifted upstairs without knowing what to do and tried to figure it out on their own, but admitted to me they’d found it confusing – so I pressed them to come during office hours for some additional instruction and help.

One library day was a simple addition to the syllabus, but I think it accomplished a lot. It got students locating and opening books. It introduced them to the resources under their noses, which–I know–they rarely consult (they Google first, and would sooner read excerpts of a book on Amazon.com than bother to see if our own library owns it). It was a teaser for the coming unit’s topics and gave them a personal connection to at least one of those topics, so maybe they’ll be looking out for that one in the upcoming classes. It made the stacks a slightly busier place in the middle of a sleepy, raw, rainy weekday. Win, win.