Our readings for this week in the Methods Course (History 411) nudged students to think about their own process of research and writing, with three complementary “how to” readings on writing history papers: a chapter from Robert C. Williams, The Historian’s Toolbox, Mary Lynn Rampolla’s A Pocket Guide to Writing in History, and “Writing the History Paper” (via the Dartmouth College Writing Program).

In discussion, we began with the “cognitive habits” of historians: how do they think? What do they think about? What kinds of questions are they concerned with? What is the “unnatural act” of thinking historically (a la Sam Wineburg)? What is “scholarly conduct” in historical writing?

From there, we moved to a discussion of the research/writing process, now that their first paper topic has mired them in the messy middle of it. We talked about how to choose, and then focus, a topic for research.

We discussed the nitty-gritty of finding things to read (search strings, chasing footnotes, navigating online databases) and I provided a handout on how to read scholarly material (“predatory reading” – this is an adapted handout from Patrick Rael’s “Predatory Reading” from Bowdoin College, which I have used in several versions across many of my classes). We discussed how “refining” or “narrowing” your topic is a constant dialogue between your research questions and your sources/evidence, an iterative process that gradually aligns your questions and sources. Lastly, we talked about taking effective research notes and about some of the advantages of moving that process, if possible, into electronic format.

My Advice on Finding Things to Read:

- Find an academic library catalog that you like (it doesn’t have to be ours, and it doesn’t have to be local) and learn to navigate it. Get to know the Library of Congress (LC) subject headings or call numbers for your topic. If you find a book that you want to read, then check to see if we own it; if not, request it from Interlibrary Loan (ILL), get it from the public library, or you may be able to read a preview on Google Books. You can also search book reviews of it, e.g. on JSTOR, to read ABOUT it, while you’re waiting for it to arrive via ILL. (Aside: my personal go-to online library is still either Brandeis or Harvard’s Widener. I’m traditional like that).

- Try physically going to a good library – a consortium library, a big public, or any large government depository library – and browsing shelves, once you know the call number area that might be productive. Even if you can’t check them out, sometimes there’s no substitute for stumbling on something in the stacks.

- Mine the footnotes of secondary sources for both primary and secondary sources. If you locate an article that looks promising, search our library’s E-Journal Finder (Articles and Databases –> E-Journal Finder) to see if we have full-text access to that article through a subscription database.

- Learn which databases tend to contain the articles you want. Try the ones listed in our library’s History Subject Guide. You can use the EBSCO database “America: History and Life” in local sister consortium libraries (Clark, Holy Cross). The best option is JSTOR, via the Boston Public Library (free to MA residents, just sign up for an e-Library card online).

- Don’t overlook newspaper and magazine archives or major newspapers (e.g. New York Times, Washington Post). For the 19th century, a good starting point is to try the magazine aggregator from Cornell University, “Making of America” or the American Memory site from the Library of Congress.

My Advice on Taking Effective Notes:

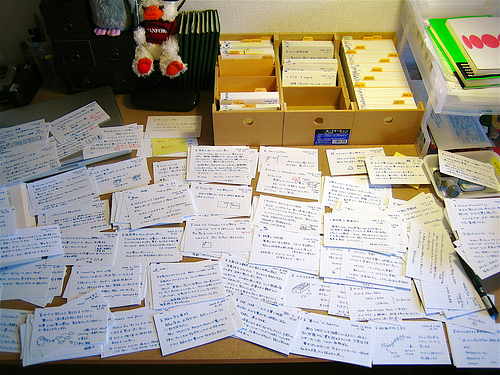

Index cards are classic (and for good reason). A notebook or research log is critical, too, to help keep your search process organized. Make sure if you are copying material, that you also remember to copy or write down the book’s complete bibliographic information so you can correctly cite it in your paper. Save your notes and/or copied material in folders, a binder, or a filebox so that it’s all in one place at your fingertips. (Aside: this is where most of my students are, still, no matter what their age: taking paper notes about paper materials).

If you’re looking for ways to automate the research process, take it online, maintain a multimedia database, back up your research in the cloud, or make it text-searchable… well then, you live in the right century, because the future is here. Some options include:

- Zotero, a free research management tool designed by scholars for scholars. Learn more about it at Zotero.org. It works as a plugin to Mozilla Firefox* and Word (or OpenOffice) and allows note-taking, tagging, organizing your “library” of sources into collections, attaching saved copies of PDFs, archiving web pages, and retrieving bibliographic information directly from a wide variety of websites as you’re conducting research (including academic libraries, Amazon.com, New York Times, Flickr, and many more). *Yes, I know about the Zotero-Everywhere coming along, but for now – I’m keeping it simple.

- StudyBlue, recently recommended by HackCollege as a useful app & the one with the best mobile capability. Haven’t used it myself, but it looks handy for note-taking.

- EverNote, similar in some ways to Zotero in its ability to archive diverse web-based resources and sort/organize them. It’s missing the Word processing bibliographic piece, but it’s a handy way to do online capture, search, and retrieval.

- OneNote, a program that often comes bundled with your typical Microsoft Office install, so you may already have it: it’s a robust note-taking and research organization tool. It’s written more for business applications but is highly adaptable to academic/scholarly ones if you play around with it a little. It allows you to create notes, folders, and virtual binders. You can’t attach or annotate PDFs or other text documents, though, so you’d need to create an “archive” folder of those materials elsewhere on your computer or on an external hard drive.

…and lastly, speaking of archiving: make sure that whatever system you adopt, that you think about how to back it up to prevent losing all your work. Some systems have this built in; if not, consider how important that is to you and develop your own alternative system of backing up your data and your writing-in-progress.

Personally, I like the (free) program called Dropbox, which instantly syncs documents across all my computers and allows me to access them from any internet connection. It has completely replaced having to carry a flash drive and eliminated the problem I used to have of having several different versions of a document on several different computer platforms. GoogleDocs is also handy that way because it constantly saves your work for you, and you have it built in when you access your Gmail. (Aside: I’m developing a workshop for the Honors program later this term called “Note-Taking for the 21st Century,” and some of this is a dry run for that session).

(Images by hawkexpress and plindberg, via Flickr. Used by Creative Commons license).