“The State of the Digital Union,” Tona Hangen, 11 Feb 2015

1) Analog to Digital

I am part of the generation who went to college and graduate school while research practices and communication modes were in the process of shifting from analog to digital. As I wrote about recently, research began with card catalogs and print periodical indexes, and later CD-ROM databases in the pre-internet but post-computer era. I didn’t own a computer of my own until well into graduate school, MIT had more than enough computer clusters for paper writing. Anyway, it’s been remarkable, the accelerating rate of change in computing, communications, and mobile technology.

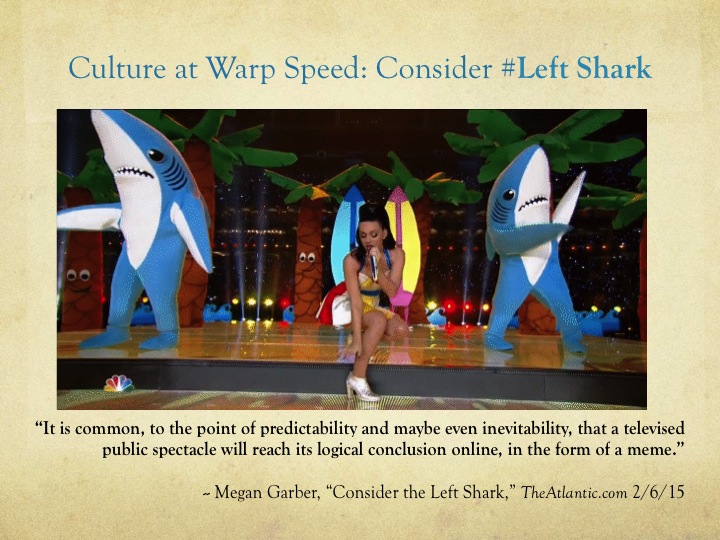

Consider, for example, the 1-week cycle of Left Shark – from appearance to internet meme to merchandizing to cease-and-desist orders to jumping the shark, all within days.

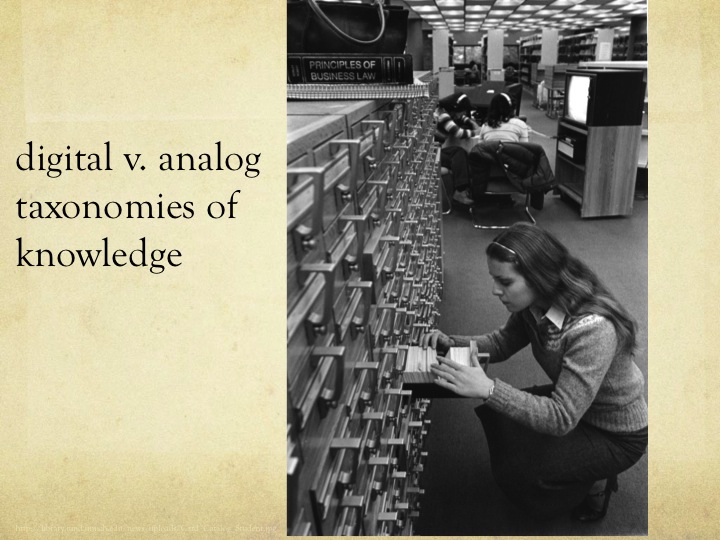

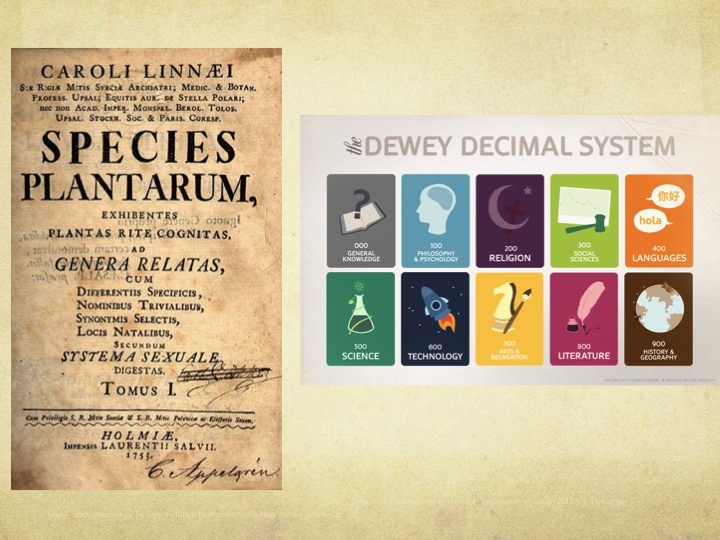

It’s not just the speed, it’s HOW knowledge is transmitted and organized, i.e. the taxonomies of knowledge that are changing. Consider analog taxonomies of knowledge, that relied on hierarchical conceptual “treesâ€

Libraries developed masterful “old†technology for managing massive amounts of data in the form of bound volumes, printed matter and other ephemera. The need for some kind of organizing schema became apparent in the 3rd century BCE, when the Library of Alexandria amassed the first big collection of texts. Alphabetical and then numerical schema came much later; James Gleick reminds us in The Information that even “a literate, book-buying Englishman at the turn of the seventeenth century could live a lifetime without ever encountering a set of data ordered alphabetically.†[1] The analog library’s magnum opus was the card catalog… elegant oak-and-brass cabinets, through which one could identify and locate any book in a library of any size, using an infinitely scalable system that created order and reproduced the analog taxonomy of knowledge in both the “drawers†and the “stacks.†All with just a typewriter and a printing press. Amazing.

The guiding metaphor of course is now the web or the network & a rather chaotic one at that. Signifiers float more freely, pinned only by association & not by location within a static knowledge system.

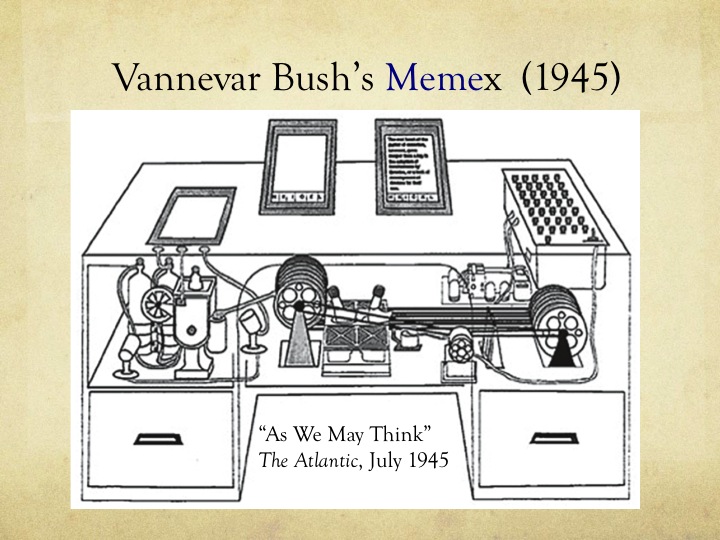

Looking back on the transition from analog to digital ways of organizing knowledge, one returns to Vannevar Bush’s article in the July 1945 issue of The Atlantic, “As We May Think,†musing on just toward what all our wartime technological research will turn, now that peace was on the horizon. He noted that manufacturing advances had ushered into the world a new “age of cheap complex devices of great reliability and something is bound to come of it.†He spoke of improving and extending existing recording processes, like photography and textual reproduction onto microformats, and proposed some version of voice-to-text transcription. He recognized that computing devices would make their way into all kinds of business and official settings. He envisioned systems to automate retail inventory that anticipated bar code scanners. But one major problem he believed researchers and scholars would be grappling with was the accelerating pace of knowledge creation, so consequently the need to transmit and review ever-larger quantities of new research, and to sort the important from the inconsequential. In that article he imagined a very special desk, which he coined the memex, where researchers could sift, skim, annotate, and organize their stacks of pre-selected reading (accessed in analog microforms. The memex (i.e. “memory†+ “index†+ “extenderâ€) would make information retrieval more intuitive and brain-like, using what Bush called “associative indexing†and helping scholars build a usefully idiosyncratic and even shareable “research trail†for their projects.

(Embedded “meme” in memex is coincidental but suggestive). Despite this all being a clever analog system, it anticipates much about the later digital world we all live in. Especially this: “(one’s) excursions may be more enjoyable if (we) can reacquire the privilege of forgetting the manifold things (we) do not need to have immediately at hand.â€

2) Where we are, Where we are not, #1

Once upon a time, last week, a Religious Studies professor at Gonzaga University sat down with several of her colleagues in an exploratory committee to figure out what digital humanities was and whether her university should be involved in it. She had in mind the beauty, elegance, and utility of an “early†DH project, dohistory.org. That site is based on the fragile and nearly illegible diary of Martha Ballard, which lives at the Maine Historical Society. The diary is now akin to an archival celebrity, but back in the day when Laurel Thatcher Ulrich began working with it, the diary was persona non grata, dismissed by other historians as “full of trivia†(but as Ulrich recounts with some relish, “That’s what I loved about it!â€). Like Kerouac’s scroll, Ballard’s unique diary rarely comes out to play in the real world, but its digital doppelganger is free to all, text searchable, fully transcribed, annotated with rich context (and yet, for all that… still with its potential largely untapped except as a pedagogical tool).

Anyway, back to the Religious Studies professor at Gonzaga. Her group began, as many exploratory groups of faculty do, with a common reading: a book. Well, a digital book, in fact, Matthew K. Gold’s edited volume from U Minnesota 2012, Debates in Digital Humanities. She describes what happened next:

We read Parts I and II for our first meeting. And when we met for the first time last week, the feeling in the room was one of frustration with the ambiguity of the term digital humanities and a lot of confusion about what even are/is #digitalhumanities.

What’s a professor to do? Take the problem to Twitter, of course.

@clark_ems 5:43pm 2/4/15 What are the best intro readings on #digitalhumanities?

By 8:51 pm, Dr. Clark had so many suggestions it became clumsy to keep all the browser windows up.

What’s a professor to do? Storify the conversation, of course.

Suppose the conversation gets richer, involves more people, and she wants it to have a more permanent presence, what’s a professor to do? Open-access publish it, of course.

I recount this little true parable, in part, because it illustrates so much about where we are, and where we’re not, with digital humanities.

Some people and institutions are all in. Some dabble on the edges. Some are frustrated, confused, and long for a single clear definition. And some have no idea what the fuss is all about. Like Vannevar Bush at the dawn of the atomic age, the age of “cheap complex devices of great reliability,†ours is also an age of transition. For previous generations, this discussion is irrelevant because they are not going to adopt new modes of digital humanities. And for generations long after ours, this discussion is meaningless because digital is the water they swim in, and know nothing else. It’s only this middle generation that needs to define, raise awareness, grind their teeth, express angst, and so on.

In 2012, Ithaka (the parent company of JSTOR) produced a qualitative white paper titled “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Historians.†Through interviewing a range of historians in detail about their research, Rutner and Schonfeld found that “the underlying research METHODS of many historians remain fairly recognizable even with the introduction of new tools and technologies, but

the day to day research PRACTICES of all historians have changed fundamentally.†[2] In other words, for historians and other humanities scholars, historical research methods and research practices are on different time tracks. And within the discipline, digital practices and methods that exploit the affordances of new digital sources are unevenly adopted, thick in some places and thin in others; the landscape is what I might call lumpy.

3) Digital Archives

Probably the most obvious and exhilarating development enabling the digital humanities – and the early hallmark of so many projects designated “digital humanities†efforts – was to simply “digitize†existing archives and publish them in electronic formats, now usually on the web (sometimes the gated web behind paywalls, sometimes the open web). The august Journal of American History began doing “website reviews†in 2001, now renamed Digital History Reviews.

As Roy Rosenzweig so succinctly put it in 2003, one effect of these digitization projects was to move historians from a world of scarcity of historical data to abundance. This was cause for celebration and utopian trumpets: the democratic promise of unmediated access to the formerly-precious evidence of the past.

But of course this kind of democracy has its downsides, starting with the toppling of professional historians as gatekeepers to and interpreters of the past.

Rosenzweig: “To open up the archives and libraries in this way democratizes historical work. Already, people who had never had direct access to archives and libraries can now enter. High school students are suddenly doing primary source research; genealogy has exploded in popularity because you no longer have to travel to distant archives. Of course, most historians would argue that, while digital collections may put ‘the novice in the archive,’ he or she is not so likely to know what to do there. Still, the balance of power may shift. Ask any travel agent how the widespread access to information undercuts professional control.†[3]

The other downside, which has become more evident over time and which necessarily occupies a lot of librarians’ and archivists’ thought these days, is the surprising fragility of digital preservation.

Rosenzweig commented presciently on this too: “Print books and records decline slowly and unevenly–faded ink or a broken-off corner of a page. But digital records fail completely–a single damaged bit can render an entire document unreadable. Here is the key difference from the paper era: we need to take action now because digital items very quickly become unreadable, or recoverable only at great expense. … the medium is far from the weakest link in the digital preservation chain. Well before most digital media degrade, they are likely to become unreadable because of changes in hardware (the disk or tape drives become obsolete) or software (the data are organized in a format destined for an application program that no longer works).â€

Furthermore, digital content’s ownership is hard to determine. And (quoting Rosenzweig again) “if libraries don’t own digital content, how can they preserve it? … Licensed and centrally controlled digital content not only erodes the ability of libraries to preserve the past, it also undercuts their responsibility. Why should a library worry about the long-term preservation of something it does not own? But then, who will?†[3]

So the second “Where we are, where we are not†is we still have not yet fully figured out how to maintain something in perpetuity which is not a unique object. And it’s not only software obsolescence that need keep us awake at night. Personal and/or institutional “digital assets†(along with digital musical downloads and social networking profiles) have questionable legal standing and tangled provenance. This reminds me of the sort-of real-world news last fall (short-lived and confirmed false within a day) that Bruce Willis was planning to sue Apple over the rights to leave his iTunes library to his children in his will. It wasn’t true, but it reminded everyone for a while of the stormy legal gray sea of digital nondurables. Hazards of the ebook age thus might include having to purchase, Groundhog-Day-like, the same digital copy over and over or works vanishing from the digital record because of copyright, both of which might be functionally equivalent to the fires and floods that used to haunt the nightmares of paper-book librarians.

4) Doing Something With Texts

So the “state of the digital union†is, I would say, “promising†but “unresolved.†Let me speak for a moment about some of the triumphs and opportunities in the digital humanities, using Obama’s 2015 State of the Union address (his sixth) as an example.

For the first time this year, the White House made the full text of the speech available online prior to his giving it (maybe because news outlets always get hold of it and leak teasers anyway). I saw some interesting things done with the text of that speech.

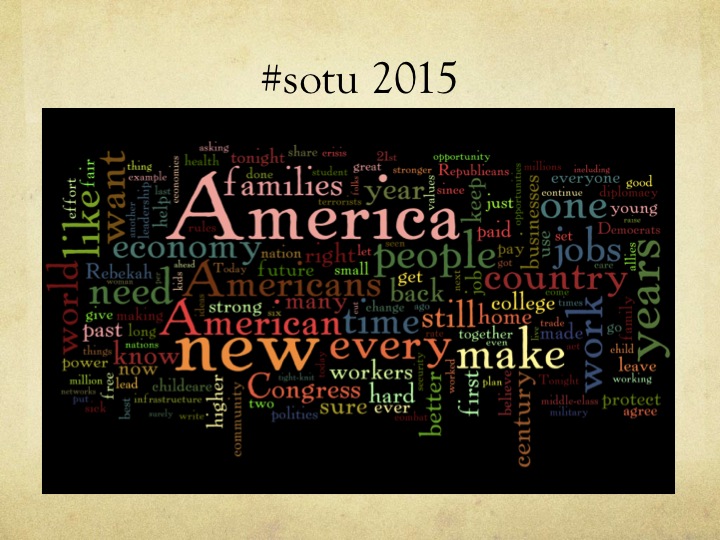

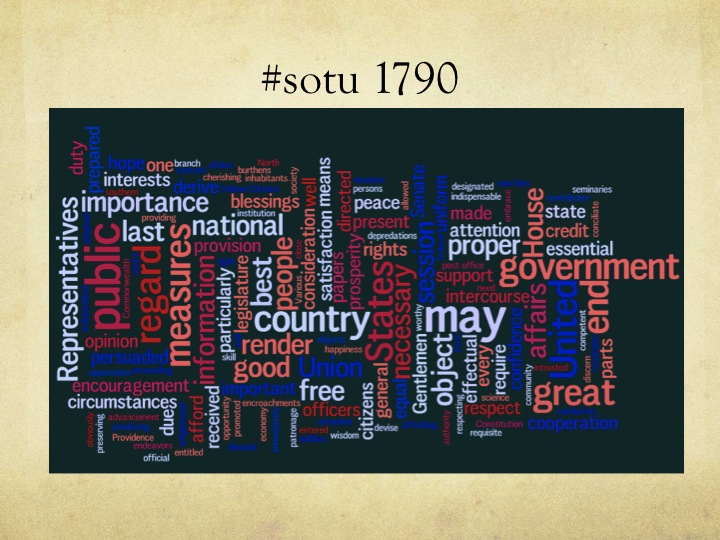

There is the by-now standard Wordle, which generates a word cloud, sizing each word by the frequency of its appearance in a given block of text. Compare Obama’s 2015 to George Washington’s 1790, for example.

But there’s more. Two digital humanists: Benjamin Schmidt, an assistant professor at Northeastern’s NU Lab for Texts, Maps and Networks and Mitch Fraas, curator at UPenn’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts built a rather beautiful interactive chart for The Atlantic exploring the frequency, date, and density of 30 keywords in all previous state of the union addresses, and then had historians comment on a few of them, including Freedom, Public, Children, Currency, War, and Her (usually referring to countries in the feminine).

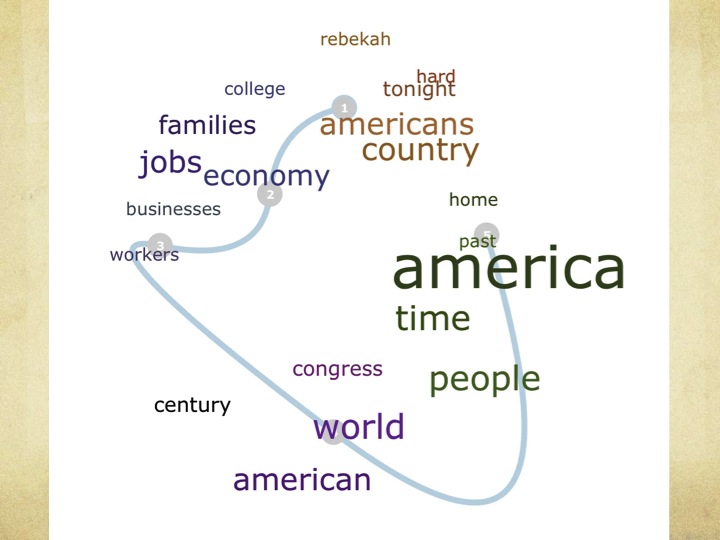

Another NU Lab professor, political scientist Nick Beauchamp, played around with other kinds of textual analysis – not just frequency of language but the shape of the argument, the structure of the speech rendered as a map. I remember how puzzled my senior capstone students were this semester when during one of our writing workshops I asked them to draw, without words, their paper’s first section or to represent it visually in some way. It immediately turned on a different (and for some, I daresay somewhat rusty) part of the brain. Beauchamp’s rhetorical “plot map†is algorithmically generated, color-coded by clusters of co-occurring words.

He describes his process:

the words and trajectory are plotted in a shared 2D space using a variant of principal component analysis. The positions of the words reflect the fact that different words can occur together or be opposed to each other: when some are mentioned, others tend not to be, and vice versa. The PCA procedure automatically infers the most dominant axes of opposition, but these oppositions often have easily interpretable meanings. In this case, we see along the horizontal dimension an opposition between broad rhetoric about America and its people on the right vs more policy-oriented discussion of the economy or world events on the left, while the domestic and international are opposed along the vertical dimension. Within that 2D word map, we can see how the speech itself moves through these topics. …. While this return to its beginnings might seem like a natural trajectory for most speeches, it is actually somewhat rare for a speech to manage such a neat circular trajectory: such a circular return requires a carefully constructed structure that revisits its beginnings on a number of different dimensions … Perhaps most interesting is how different variants of America appear in different places. It is common in text analysis to collapse all variants of a word into a single stem, but this speech illustrates how that can hide important distinctions.

And Beauchamp’s made it available so you can try it with other texts for yourself.

And the Sunlight Foundation created a “SOTU Generator†based on language modeling from previous presidents, with sliders to put more of one president & less of another into your auto-generated speech. Fun, but also seriously instructive about language and personality in politics.

Tools like this one showcase the best of what digital humanists are building to analyze texts, aggregate data, search across vast oceans of words, and display the results in ways that are visually stunning and sometimes revelatory in and of themselves – or which generate curiosity and invite play instead of simply display predetermined results.

Another couple of examples: quick demo of Bookworm (the tool they used to create the Atlantic word frequency chart), Trove’s Query Pic, Google N-Gram, the Popular Science Archive Explorer, and Baby Name Voyager.

5) Calling in Reinforcements

One of the liveliest developments in digital humanities recently is an uptick in the popularity of crowdsourcing, especially for transcription and tagging – tedious tasks that nonetheless can’t be outsourced to bots or programs. I’ll just highlight a few –

Smithsonian Digital Volunteers

DIY History – U Iowa Libraries

NYPL Menus

FamilySearch indexing (effort from my own faith community, transcribing vital records in many languages)

These projects generate public engagement and help spread the work (but add another level of curator scrutiny after public transcription), and have opened up fascinating collections. I’ve used them in the absence of a University Special Collections to give students experience with deciphering longhand manuscripts in our methods course.

One of the benefits of crowdsourced projects is to broaden the number of people and perspectives involved in looking at and marking up a group of documents. The wider that net is cast, the richer and more diverse the possible interpretations and uses.

Metadatagames.org enlivens this process by making a game out of crowdsourcing metadata for a wide variety of mainly non-textual sources drawn from archives and libraries: images, audio, moving images. Built at Dartmouth. Quoting from their site, “The platform [which is open-source, BTW] entices players to visit archives and explore humanities content while contributing to vital records. The suite enables archivists to gather and analyze information for digital media archives in novel and exciting ways.†Games include: Zen Tag, One Up, Guess What, Stupid Robot, NexTag and Pyramid Tag. Some as downloadable apps, others as games within the browser.

6) Locating items in something other than “cyberspaceâ€

Metadatagames and other crowdsourced projects, as fun as they are, tend to observe items in isolation, removing them from their context, make them into cryptic zeppelins drifting in cyberspace subject to multiple interpretations, some of which will be valuable and others will be just plain off-base.

So, let’s ascend another ridge in the digital humanities landscape to geolocation, mapping, and timelines – ways to locate historical data in time and space. One such project under development at UVA’s Scholars Lab, called Neatline, has “the ability to link maps and timelines to digitized humanities collections,†and to include multimedia, interactive, or nonlinear elements as part of digital storytelling.

As Scholars Lab director Bethany Nowviskie explains, Neatline also “built in the capacity for the tool to support multiple—even conflicting or contested—stories told on top of the same archival collection. This means that different scholars or students can make their own arguments using the same set of materials, or a single scholar can try out multiple, differing interpretations or theses. That’s the way humanities interpretation works, after all.â€

UVA’s Neatline and their efforts to connect the digital and archival worlds in authentic contexts of scholarly discourse reminds us of another of these “where we are, where we are not†milestones – digital humanities are the humanities, intrinsically linked to the physical, embodied, tangible realities they seek to understand.

As Nowviskie puts it, “for a long time there was a “cyberspace†stereotype about my field—that digital humanities happened in a completely artificial, online world, divorced from real bodies and lived experience. That argument’s just not possible anymore. The ubiquity of mobile, wearable, and embedded devices, mass digitization of the print record, the study of the history of science and technology, the advent of 3D printing, the rise of augmented reality and social media—all of these things demonstrate how the physical and digital have always interpenetrated each other and are now even more obviously part of a cycle or continuum.â€

7) Building Things

One underlying ethic of the digital humanities is the hacker, or maker, ethic. I see this as deeply connected to the re-emergence of craft in the broadest sense, our 21st century renaissance of the Arts and Crafts movement, from DIY hobbying to “crafting†of all kinds, to cosplaying, steampunk, Etsy, Kickstarter micro-manufacturing, locavore eating and craft foods, all part of a vibrant and growing counterculture challenging homogenized mass culture, corporate box-stores, and chain restaurants. Each of the craft movements I mentioned in some ways rejects technology, but in other ways is inseparably dependent upon it and could not have arisen except in that context.

So I think my next “where we are, where we are not†point is that the digital humanities are about building, and in particular, despite all the beautiful things we can do with texts, finding ways to explore and create non-textual sources.

One small example: the religious soundscape project documenting religious diversity in the Midwest, headed up by Amy DeRogatis at Michigan State U. Another: Stanford’s efforts to make a newly-acquired collection of player piano rolls (not mass-produced, but ones that captured the player’s unique performance) accessible through MIDI files.

Stephen Ramsay practically incited a riot among the black-suited academic hipsters at MLA in 2011 in the provocative panel “History and Future of Digital Humanities.†He said, rather audaciously (he’d been given exactly 3 minutes, in a classic digital humanities “disruptive†panel structure):

Personally, I think Digital Humanities is about building things. I’m willing to entertain highly expansive definitions of what it means to build something. I also think the discipline includes and should include people who theorize about building, people who design so that others might build, and those who supervise building. I’d even include people who are working to rebuild systems like our present, irretrievably broken system of scholarly publishing. But if you are not making anything, you are not — in my less-than-three-minute opinion — a digital humanist. You might be something else that is good and worthy — maybe you’re a scholar of new media, or maybe a game theorist, or maybe a classicist with a blog (the latter being very good thing indeed) — but if you aren’t building, you are not engaged in the “methodologization†of the humanities, which, to me, is the hallmark of the discipline that was already decades old when I came to it.

So what then distinguishes digital humanists from commercial builders? It’s the questions they bring to the work, and the purposes for which they build. Even kids can increasingly think of the digital world as a place to build; witness the fascinating article this week in The Atlantic about how Minecraft construction projects are, for some kids, replacing the shoe-box diorama as a way to represent their academic learning in spatial dimensions. The links in that article, by the way, introduced me to the news that the entire country of Denmark has now been built in Minecraft, a scale version of their entire country made by two employees at the Danish Ministry of the Environment’s Geodata Agency. They made it after the Danish government made its environmental data public and downloadable for free last year “as part of an open data push.†Why? Mainly “because they could.†And when we try things we CAN do, we often generate new questions or learn something fresh in the process and in the results.

Building includes curating, or making exhibits, i.e. public history. And here is where the internet has left the professional gatekeepers in the electrostatic dust. From conspiracy websites to Pinterest, people “make history†across the web on high wires without the safety net of peer review, footnotes, or accountability. Again – there is democratic promise here, but also a bit of the wild West.

Consider this built, lost & found digital object. It’s called “Take Me Back to the Fifties†(http://oldfortyfives.com/TakeMeBackToTheFifties.htm). I have watched it literally dozens of times with classes, because it so neatly captures boomer nostalgia for the 1950s, and each time it puzzles and intrigues me a little more as an example of amateur digital storytelling. It’s about as far as one can get from academic narrative. Take some notes.

It’s now gone from the web (RIP OldBlueWebDesigns), so we have to use the Internet Archive’s wayback machine to find it (which just proves my earlier point about the instability of the internet as a repository for digital history).

https://web.archive.org/web/20120317095436/http://oldfortyfives.com/TakeMeBackToTheFifties.htm – allow 7:30 minutes and turn on your sound

What a piece of work! The Comic Sans font. The gifs. The floating, spinning words. Juxtaposition of images. Bizarrely uneven narrative. Authorial anonymity. So much to unpack there. Questions for group discussion, similar to those I would ask my students about any primary source they’re meeting for the first time.

Discussion – Categorization – What is it? How was it made? Relationship between medium and message? What is it for originally? What could historians use it for? What’s its provenance? Metadata? Is this digital history?

I want to argue that this IS digital history. Granted it’s of the folk / vernacular / lowbrow variety, but how many humanistic scholars (myself included) make their living from trying to understand the culture of ordinary people in the past? Exactly. And maybe we historians have something to learn from what Dan Cohen calls the “vernacular web” in terms of storytelling, audacity, and going for broke.

8) Stop Calling it DH Already(?)

Some digital humanities scholars are already looking past the transitional era, to when digital practices and methods are just part of the humanities toolbox without having to put the word “digital†in neon.

Ryan Cordell at Northeastern talks about how a course he proposed for one university, “Doing Digital Humanities†flopped because it took digital humanities as the object ITSELF of study, but when he took the same methods and made them the necessary tools for solving a particular problem, in a course re-named “Texts, Maps, Networks,†it worked.

He clarifies: “students do love doing DH things, when those DH things are framed around particular skills and often within disciplinary structures. And I would argue more and more that the way we should integrate DH into the undergraduate curriculum is as a naturalized part of what literary scholars or historians or other humanists do.â€

Has the term lost its utility? Not yet, according to Cordell: “digital humanities remains a useful banner for gathering a community of scholars doing weird humanities work with computers.”

Similarly, here’s William Pannapacker, a guru in the field and an English professor at Hope College, in a recent essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education titled “Stop Calling it Digital Humanities“: “As an umbrella term for many kinds of technologically enhanced scholarly work, DH has built up a lot of brand visibility, especially at research universities. But in the context in which I work, it seems more inclusive to call it digital liberal arts (DLA) with the assumption that we’ll lose the ‘digital’ within a few years, once practices that seem innovative today become the ordinary methods of scholarship. DH is not a ‘disruption’ — it is an enhancement of the core methods of an ideal liberal-arts education.â€

And – witness the fascination of my kids and their cousins at Christmas this year, when we gifted our college son a record player; the death of analog has been greatly exaggerated.

9) A Call to Arms, But Also Brains

The seal of my alma mater (MIT) represents Mens et Manus (i.e. Mind and Hand). Thinking and Doing. Brain and Brawn. Code and Bodies. Digital and Humanities.

I think it’s important to recognize both are needed. In his massive history, The Information, science historian James Gleick notes: “Facts were once dear; now they are cheap.†And “when information is cheap, attention is expensive.†What becomes more vital is the process knowledge of how to cope with giant data, make sense from jumble, create stories from chaotic noise. Libraries and archives, as well as what we call on the internet search “engines†(evoking massive steampunk cogs, an industrial metaphor for the post-industrial age) provide the two essential coping strategies in the age of information abundance; filter (blog, aggregate, curate) and search (retrieve binary text-string needles from digital haystacks). These functions cannot be left exclusively to the free market; cultural curators, educators, and keepers of library flames must be more than hirelings of “the next big thing.â€

Digital humanists (as with all humanities scholars) must be willing to be nimble, “experimental, playful.†Lisa Spiro (then) of NITLE encourages us to “ground your learning in a specific project and find insightful people with whom you can discuss your work.†Dan Cohen (now) of DPLA wrote back in 2010: “I would like to advance this principle: Scholars have uses for edited collections that the editors cannot anticipate. One of the joys of [his project the September 11 Digital Archive’s] server logs is that we can actually see that principle in action (whereas print editorial projects have no idea how their volumes are being used, except in footnotes many years later). In the September 11 Digital Archive we assumed as historians that all uses of the archive would be related to social history. But we discovered later that many linguists were using the archive to study teen slang at the turn of the century, because it was a large open database that held many stories by teens. Anyone creating resources to serve scholars and scholarship needs to account for these unanticipated uses.â€

I heard a relevant fascinating story from NPR’s Planet Money podcast recently, in which they dubbed this phenomenon the “technology tango.†Technology allows creators to make something; users modify it, stretching the limits of that technology; creators respond by adapting, too. In commercial terms, they looked at the case study Chinese gaming website yy.com, which began as an online gaming platform. To help gamers whose hands were busy, they created a high-quality audio component so gamers could talk to each other without typing. Some then began to use it kind of like Skype, to communicate with friends who were also online. Then young girls began to create personalized karaoke “channels.†So yy.com added the ability to rate, vote for, and reward these performers with emojis and it turns out, that was yy.com’s eventual revenue stream and (as you can see from a screenshot of the site this week), this undreamt use has basically taken over the site.

This business model case study has applications in the digital humanities, too. As we’re building out this world together, scholars and librarians and archivists and amateurs and genealogists and storytellers, let us continue to tango. Here’s to unanticipated uses and crowdsourced solutions and collaborative building and mucking about with code. This week’s sobering news, from Syria and Ukraine and Chapel Hill, reminds us of the urgency of the task of understanding the human endeavor better, and of bringing both mind and hand to bear on the essential problems and questions that drive all of the humanities. The work of historians and scholars has never been more important.

Notes

[1] James Gleick, The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood (Pantheon, 2011), 59.

[2] Jennifer Rutner and Roger G Schonfeld, Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Historians (Ithaka S+R, 2012).

[3] Roy Rosenzweig, “Scarcity or Abundance: Preserving the Past in a Digital Era,” American Historical Review 108, 3 (June 2003): 735-762.

Links/strong>

“Language of the State of the Union,” The Atlantic 1/18/2015

Nick Beauchamp’s Plot Mapper http://nickbeauchamp.com/projects/plotmapper.php

State of the Union Generator (Sunlight Foundation) http://sotu.sunlightfoundation.com/s/28f73693

Bookworm http://bookworm.culturomics.org/

Google N-Gram Viewer https://books.google.com/ngrams

Popular Science Archive Explorer http://www.popsci.com/content/wordfrequency#internet

Trove / Query Pic http://dhistory.org/querypic/

Baby Name Voyager http://www.babynamewizard.com/voyager

DIY History, University of Iowa Libraries http://diyhistory.lib.uiowa.edu/about

Smithsonian Digital Volunteers https://transcription.si.edu/

FamilySearch Indexing Projects https://familysearch.org/indexing/

NYPL Menus Project http://menus.nypl.org/

Neatline http://neatline.org/

Metadata Games http://www.metadatagames.org/

History on Pinterest https://www.pinterest.com/categories/history/

Further Resources

Twitter List: DH Movers and Shakers

https://twitter.com/tonahangen/lists/dh-movers-and-shakers

Miriam Posner, “How Did They Make That?†– 8/29/2013

http://miriamposner.com/blog/how-did-they-make-that/

Erin Bush (George Mason University) Reading List for Minor in Digital History, May 2009

http://erinbush.org/minor-field-digital-history/

“Doing Digital History” / George Mason + NEH Summer Institute 2014 – Especially the lists of Readings, Resources, Sites and Tools

http://history2014.doingdh.org/readings/

Follow along with Lincoln Mullen’s Spring 2015 course at George Mason, “The Digital Pastâ€

http://lincolnmullen.com/courses/digital-past-2015/

Lisa M. Spiro (NITLE), Getting Started in the Digital Humanities

https://digitalscholarship.wordpress.com/2011/10/14/getting-started-in-the-digital-humanities/ (terrific, although it’s from 2011 so some links no longer live)

DIRT – Digital Research Tools

http://dirtdirectory.org/